The Age of Anxiety in the 20th Century: Reflections in the Early Modern Works of Dalí, Höch, and Picasso

The early 20th century was an era like no other, marked by dizzying advancements in technology, massive shifts in social norms, and devastating global conflicts. People’s lives were constantly shifting under the weight of change, creating a sense of uncertainty and dread, known as the “Age of Anxiety.” Artists at the time channeled this tension into their work, creating pieces that reflect this collective unease. Three powerful works, Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory (1931), Hannah Höch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919-1920), and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), capture this anxiety in different but equally unsettling ways. Through surrealism, Dada, and cubism, each artist conveys the chaos, fragmentation, and anguish that defined this era.

Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory is often described as “haunting” and “mesmerizing.” Painted in 1931, it shows us a bizarre landscape where time seems to have literally melted away. According to Smarthistory, Dalí’s melting clocks evoke “the sensation of time slipping away,” a feeling many people in the 1930s could relate to as the world around them changed at a terrifying pace. The landscape feels empty and lonely, almost as if we’re looking into a dream or a distant memory. Dali uses a muted color palette with warm brown and beige tones in the foreground contrasting with cooler blues in the background. The fluid forms, especially the melting clocks, paired with the seemingly manmade structures, like the right-angled platform the dead tree stands on, defy natural structure and order. These clocks symbolize the collapse of stable time and certainty, a fitting metaphor for the anxieties of society. Dalí’s landscape is arranged sparsely, with empty space surrounding the few objects.

Dalí once said his work was like a “hand-painted dream photograph.” And that’s exactly what we see here, a surreal vision of time melting into nothingness. The barren setting and empty space make the viewer feel isolated, reflecting the existential loneliness that so many people felt during that unpredictable time. As with dreams, almost every part of this painting makes no sense, yet holds a symbolic meaning. We see ants gathered together to eat the metal pocket watch on the bottom left, and a figure in the shape of what could be a face lying on the ground. One moment, the viewer may think they know what they are looking at, only to realize that they actually don’t.

Dalí’s work is steeped in Freudian psychoanalysis, which reflects society’s growing interest in the subconscious and the mysteries of the human mind. The Museum of Modern Art notes that Dalí was fascinated by dreams and the psyche, which he explored through his “journey into the unconscious”. According to historian Barbara Ehrenreich, Dalí’s piece captures the alienation of modern individuals who felt increasingly disconnected from the world due to technological advancements and shifting social structures.

Höch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife is as chaotic as its title. What first looks like a random collage, this 1919–1920 photomontage captures the fractured state of Weimar Germany after World War I. Created in the spirit of Dada, a movement that rejected conventional art and embraced absurdity, Höch’s work critiques the social and political turmoil of her time. Smarthistory says that her photomontage is “a searing commentary on the disordered society she lived in”. It’s packed with overlapping, torn images of politicians, cultural icons, and industrial symbols.

The fragmented and overlapping forms in Höch’s photomontage give off a sense of overwhelming confusion and disorder. The dense arrangement and jagged edges reflect the societal breakdown of post-war Germany, showcasing the instability that plagued people’s lives. The viewer’s eye is forced to jump around the piece, mirroring the anxiety and disorientation that people felt during this period. It’s unsettling and almost dizzying to look at, which only strengthens its message about the madness of the times. The collage is filled with images of politicians and symbols of industrial progress, critiquing the political establishment and the growing influence of mechanization. Höch’s choice of symbols, often absurd and grotesque, reflects her skepticism toward authority and modernity. While seemingly random, we realize that each item was carefully selected to showcase her stance on women artists. In this Dadist version of “Where’s Waldo”, you can find a cut out of Hannah’s head placed within the piece, in place of her signature. It’s said that its placement on the map, “shows the countries in Europe that had women’s voting rights at the time.”

Leah Dickerman, a Dada scholar, suggests that Höch’s work captures a “breakdown of logic” and the rejection of traditional structures, which is reflective of the anxious, disillusioned public. The Tate Gallery adds that Höch’s collage embodies a “political and social critique” relevant to her time, touching on the collective discontent that followed the war.

Picasso’s Guernica, painted in response to the bombing of a Spanish town during the Spanish Civil War, is a raw, emotional depiction of suffering. The monochromatic, distorted figures convey pain, suffering, and terror, capturing the anguish of innocent civilians caught in the violence of war. In a Smarthistory article, art historian Lynn Robinson describes Guernica as “a cry of pain and outrage,” embodying Picasso’s anti-war sentiment and his empathy for innocent civilians. In this painting, we see a mother wailing at the sky as she holds her dead child, severed limbs, broken swords, and people fleeing from and burning in buildings. A scene that is horrific to observe, yet pales in comparison to the actual event.

Guernica is claustrophobic, with bodies and shapes pressed close together, creating a feeling of suffocation. Picasso’s use of cubist distortion turns recognizable figures into exaggerated shapes, making the viewer feel the depth of their suffering. It’s hard not to feel overwhelmed by the sheer chaos of the scene, and that’s exactly what makes this painting so powerful. Picasso uses a stark black-and-white scheme to suggest the stripping away of humanity and innocence. It’s as if Picasso is forcing us to look directly at the devastation of war and the helplessness it creates. The exaggerated forms and anguished faces create a visceral response, evoking our empathy and distress as viewers are drawn into the agony of the scene.

Dalí, Höch, and Picasso each present a unique vision of the early 20th century’s anxieties, yet their works share an unsettling quality that brings the era’s struggles to life. Through surrealism, Dada, and cubism, these artists explore themes of time, societal breakdown, and war, painting an emotional portrait of a time when the world felt unpredictable and frightening.

Personally, I find this era of art my least favorite. I can appreciate the artists’ attempts to capture the world’s dissonance, confusion, and anxiety, but I wouldn’t want these works in my home. There’s an undeniable sense of unease in them, an unsettling feeling that lingers. While I can see the artistic merit and importance of these works, they’re not pieces that would bring me comfort or joy.

Works Cited:

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). “Salvador Dalí. The Persistence of Memory. 1931.” MoMA Learning, The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed November 1, 2024. www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/salvador-dali-the-persistence-of-memory-1931.

Tate. “Hannah Höch.” Tate, The Tate Gallery. Accessed November 1, 2024. www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/hannah-hoch-1263.

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. “Guernica by Pablo Picasso.” Reina Sofía Collection, Museo Reina Sofía. Accessed November 1, 2024. www.museoreinasofia.es/en/collection/artwork/guernica.

Robinson, Lynn. "Pablo Picasso, Guernica." Smarthistory, August 9, 2015. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://smarthistory.org/picasso-guernica/.

Barber, Dr. Karen. "Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany." Smarthistory, August 18, 2020. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://smarthistory.org/hannah-hoch-cut-kitchen-knife-dada-weimar-beer-belly-germany/.

Khan, Sal, and Dr. Steven Zucker. "Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory." Smarthistory, December 9, 2015. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://smarthistory.org/salvador-dali-the-persistence-of-memory/.

Salvador Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory

Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory, 1931, oil on canvas, 24.1 x 33 cm (Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory is often described as “haunting” and “mesmerizing.” Painted in 1931, it shows us a bizarre landscape where time seems to have literally melted away. According to Smarthistory, Dalí’s melting clocks evoke “the sensation of time slipping away,” a feeling many people in the 1930s could relate to as the world around them changed at a terrifying pace. The landscape feels empty and lonely, almost as if we’re looking into a dream or a distant memory. Dali uses a muted color palette with warm brown and beige tones in the foreground contrasting with cooler blues in the background. The fluid forms, especially the melting clocks, paired with the seemingly manmade structures, like the right-angled platform the dead tree stands on, defy natural structure and order. These clocks symbolize the collapse of stable time and certainty, a fitting metaphor for the anxieties of society. Dalí’s landscape is arranged sparsely, with empty space surrounding the few objects.

Dalí once said his work was like a “hand-painted dream photograph.” And that’s exactly what we see here, a surreal vision of time melting into nothingness. The barren setting and empty space make the viewer feel isolated, reflecting the existential loneliness that so many people felt during that unpredictable time. As with dreams, almost every part of this painting makes no sense, yet holds a symbolic meaning. We see ants gathered together to eat the metal pocket watch on the bottom left, and a figure in the shape of what could be a face lying on the ground. One moment, the viewer may think they know what they are looking at, only to realize that they actually don’t.

Dalí’s work is steeped in Freudian psychoanalysis, which reflects society’s growing interest in the subconscious and the mysteries of the human mind. The Museum of Modern Art notes that Dalí was fascinated by dreams and the psyche, which he explored through his “journey into the unconscious”. According to historian Barbara Ehrenreich, Dalí’s piece captures the alienation of modern individuals who felt increasingly disconnected from the world due to technological advancements and shifting social structures.

Hannah Höch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany

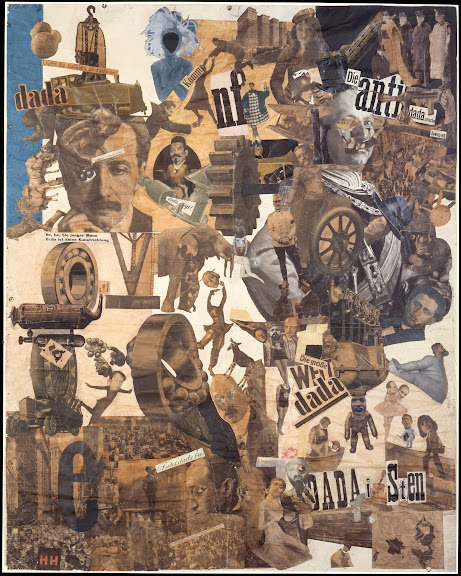

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919–1920, collage, mixed media, (Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin)

Höch’s Cut with the Kitchen Knife is as chaotic as its title. What first looks like a random collage, this 1919–1920 photomontage captures the fractured state of Weimar Germany after World War I. Created in the spirit of Dada, a movement that rejected conventional art and embraced absurdity, Höch’s work critiques the social and political turmoil of her time. Smarthistory says that her photomontage is “a searing commentary on the disordered society she lived in”. It’s packed with overlapping, torn images of politicians, cultural icons, and industrial symbols.

The fragmented and overlapping forms in Höch’s photomontage give off a sense of overwhelming confusion and disorder. The dense arrangement and jagged edges reflect the societal breakdown of post-war Germany, showcasing the instability that plagued people’s lives. The viewer’s eye is forced to jump around the piece, mirroring the anxiety and disorientation that people felt during this period. It’s unsettling and almost dizzying to look at, which only strengthens its message about the madness of the times. The collage is filled with images of politicians and symbols of industrial progress, critiquing the political establishment and the growing influence of mechanization. Höch’s choice of symbols, often absurd and grotesque, reflects her skepticism toward authority and modernity. While seemingly random, we realize that each item was carefully selected to showcase her stance on women artists. In this Dadist version of “Where’s Waldo”, you can find a cut out of Hannah’s head placed within the piece, in place of her signature. It’s said that its placement on the map, “shows the countries in Europe that had women’s voting rights at the time.”

Leah Dickerman, a Dada scholar, suggests that Höch’s work captures a “breakdown of logic” and the rejection of traditional structures, which is reflective of the anxious, disillusioned public. The Tate Gallery adds that Höch’s collage embodies a “political and social critique” relevant to her time, touching on the collective discontent that followed the war.

Pablo Picasso’s Guernica

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, oil on canvas, 349 x 776 cm (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía)

Picasso’s Guernica, painted in response to the bombing of a Spanish town during the Spanish Civil War, is a raw, emotional depiction of suffering. The monochromatic, distorted figures convey pain, suffering, and terror, capturing the anguish of innocent civilians caught in the violence of war. In a Smarthistory article, art historian Lynn Robinson describes Guernica as “a cry of pain and outrage,” embodying Picasso’s anti-war sentiment and his empathy for innocent civilians. In this painting, we see a mother wailing at the sky as she holds her dead child, severed limbs, broken swords, and people fleeing from and burning in buildings. A scene that is horrific to observe, yet pales in comparison to the actual event.

Guernica is claustrophobic, with bodies and shapes pressed close together, creating a feeling of suffocation. Picasso’s use of cubist distortion turns recognizable figures into exaggerated shapes, making the viewer feel the depth of their suffering. It’s hard not to feel overwhelmed by the sheer chaos of the scene, and that’s exactly what makes this painting so powerful. Picasso uses a stark black-and-white scheme to suggest the stripping away of humanity and innocence. It’s as if Picasso is forcing us to look directly at the devastation of war and the helplessness it creates. The exaggerated forms and anguished faces create a visceral response, evoking our empathy and distress as viewers are drawn into the agony of the scene.

Dalí, Höch, and Picasso each present a unique vision of the early 20th century’s anxieties, yet their works share an unsettling quality that brings the era’s struggles to life. Through surrealism, Dada, and cubism, these artists explore themes of time, societal breakdown, and war, painting an emotional portrait of a time when the world felt unpredictable and frightening.

Personally, I find this era of art my least favorite. I can appreciate the artists’ attempts to capture the world’s dissonance, confusion, and anxiety, but I wouldn’t want these works in my home. There’s an undeniable sense of unease in them, an unsettling feeling that lingers. While I can see the artistic merit and importance of these works, they’re not pieces that would bring me comfort or joy.

Works Cited:

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). “Salvador Dalí. The Persistence of Memory. 1931.” MoMA Learning, The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed November 1, 2024. www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/salvador-dali-the-persistence-of-memory-1931.

Tate. “Hannah Höch.” Tate, The Tate Gallery. Accessed November 1, 2024. www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/hannah-hoch-1263.

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. “Guernica by Pablo Picasso.” Reina Sofía Collection, Museo Reina Sofía. Accessed November 1, 2024. www.museoreinasofia.es/en/collection/artwork/guernica.

Robinson, Lynn. "Pablo Picasso, Guernica." Smarthistory, August 9, 2015. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://smarthistory.org/picasso-guernica/.

Barber, Dr. Karen. "Hannah Höch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Dada Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany." Smarthistory, August 18, 2020. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://smarthistory.org/hannah-hoch-cut-kitchen-knife-dada-weimar-beer-belly-germany/.

Khan, Sal, and Dr. Steven Zucker. "Salvador Dalí, The Persistence of Memory." Smarthistory, December 9, 2015. Accessed November 1, 2024. https://smarthistory.org/salvador-dali-the-persistence-of-memory/.

I appreciate the deep emotional resonance and psychological exploration in the works of Dalí, Höch, and Picasso, particularly how they articulate the collective anxiety of the early 20th century. Each piece reflects a different facet of this theme—Dalí's fluidity of time, Höch's chaotic critique of society, and Picasso's visceral depiction of war—effectively capturing the overwhelming uncertainty of the era. However, while powerful, the disquieting nature of their works can also be off-putting; the feelings of isolation and despair they evoke are not what I seek in art. This tension between appreciation for their artistic genius and a desire for more comforting themes highlights the complexities of engaging with art and confronting uncomfortable truths. Ultimately, these artists serve as crucial reminders of the emotional landscapes shaped by historical events, pushing us to confront rather than escape the darker aspects of our shared humanity.

ReplyDeleteWhat draws me to Salvador Dalí's The Persistence of Memory is not just its exploration of memory, primarily through the warped clocks, but also the unsettling yet captivating nature of his art. The warped clocks give off this strange feeling of time melting away, which connects with the existential themes of the early 20th century. The emptiness of the desert landscape adds to a sense of isolation and disconnection, reflecting what many people went through during that chaotic time. When I think about my trip to Europe last year, the visit to the Salvador Dalí exhibit in Bruges sticks out. I was blown away by how provocative his art is. Some pieces genuinely unsettled me, like The Great Masturbator, which dives into complex themes of sexuality and those Freudian ideas we’ve covered in psychology. Dalí has this incredible knack for mixing the surreal with deep psychological insights, making his commentary on the human experience both unsettling and captivating.

ReplyDeleteThere's such a strong sense of anguish and uncertainty in the works discussed. I thought including Picasso's Guernica was compelling—it captures the intense anxiety of the Spanish Civil War. The chaotic shapes and distorted figures paint a vivid picture of the devastation that war brings to innocent people. It’s incredible how art can react so directly to deep feelings of fear and turmoil, revealing not just the artists' perspectives but also the shared distress of society. This connection between anxiety and artistic expression shows how closely our emotions are tied to the world around us.

I also appreciate you bringing up Hannah Höch in your analysis. Her work, especially in Cut with the Kitchen Knife, offers a unique perspective on the societal upheaval in post-World War I Germany. After looking more into her art, I admire how she uses colour and collage to critique the government and address the gender roles of her time. The way she layers images creates a visual complexity that reflects society's disarray. Höch’s vibrant colours and dynamic forms starkly contrast some of the darker themes in Dalí's and Picasso's works. Yet, she still tackles similar anxieties about identity and societal structure. This enriches our understanding of how different artists responded to the challenges of their time, showcasing the diverse voices and experiences that characterised the "Age of Anxiety."

I like how you tied The Persistence of Memory to the general anxiety of the time and how you related the imagery to the feeling of time slipping away. I have the same feelings when I look at the piece so I can imagine how those may have felt after just going through a massive war and having events occur that point to another on the horizon. I'm also a fan of Guernica and your choice to include it, fitting well with the theme of anxiety and suffering. The choice to use only black and white colors really adds to the violence and pain portrayed in the image. Additionally the gaping expressions on the figures' faces works well to convey noise and chaos within the piece. Great choices and thanks for sharing!

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteI really enjoyed your synopsis on the anxious time period the early 20th century was. Dali’s work was a perfect painting to represent the fearful time they lived through. It seems there are a lot of similarities in the sentiment we have towards our own time period now and theirs. It feels like time is both frozen and rapidly accelerating conjointly. I love that you brought up the alienation people felt with the advancement of technology and their changing world. America and western european nations had become very urbanized by the 1920s and new technologies created great generational divides between how someone lived compared to their parents, how they grew up, and how the world their children would grow up in. Hoch’s piece was another great choice. Absurdity is a great commentary on the world and seems to reach across to both progressives and conservatives alike. During this time there was a great disconnect as to how to rebuild Europe. Many longed for the past Victorian and Romantic era of unity and prosperity after the Great War but others were embracing this as a time to rebuild an entirely new society. The rise of Communism and Fascism and many other political and economic movements sprouted up during this time. Dada seems to me like a unifying art movement that at first glance seems like a a criticism of the instability of the time while propping up these voices of change. Highlighting the women’s suffrage movement through highlighting the countries that allowed women to vote is definitely a good example of this, I’m glad you brought it up.

Hi! I love your descriptions of the artwork. Out of all the styles that you have presented I think the one that I find the most interesting is the Dada.

ReplyDelete